Touch screens, holograms, and scaled models to learn about Spanish participation in the exploration of our closest planetary neighbor.

Science communication has always been one of the main areas of interest for SpaceRobotics.EU. Since we began working on our project we’ve participated in countless science communication events and we’ve designed and built with our own hands lots of hardware for museum modules and temporal exhibitions. In this area, our latest accomplishment is”Spain in Mars”, a brand new exhibition about the Spanish presence on the red planet. This exhibition was fully developed by us and it features scaled models built with our latest 3d-printing technologies, no-glasses-required holograms, and touch-screen software with some really cool features.

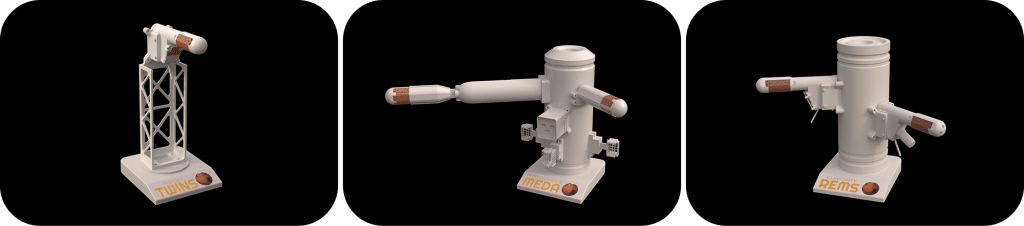

The super-detailed scaled models represent REMS, TWINS and MEDA, three weather stations onboard the Curiosity, InSight and Perseverance missions respectively. All these stations are currently operating on Mars, and all three of them were designed and built in Spain by the Astrobiology Centre “CAB”. These stations are packed with state of the art thermometers, barometers, and anemometers as well as humidity, radiation, and dust sensors. The data they retrieve is helping us better understand the red planet, its history, its atmosphere, and the important role that dust plays in it. Also, this data is showing us now the conditions we could meet in future human explorations.

Additional scaled models represent the full Curiosity, InSight, and Perseverance landers, as well as the Ingenuity “helicopter” and some other pieces. All these 3D models are also represented in our no-glasses-required 3D holograms, which display the instruments floating right in front of the visitor.

The touch-screen software features information about these weather stations and the missions they accompany. This information is accessible through an interactive user interface full of images and 3d models that also let the visitors connect with these stations in real time to check out the weather on Mars. Furthermore, additional screens host Mars-related minigames for the visitor to enjoy and learn from. My favorite is the one where you have to guess for each image if it was taken from Mars or the Earth. Easy, right? Well, it’s way harder than it sounds. Some Earth landscapes are really similar to Mars’.

We first built the exhibition at Expoastronómica 2022. It was a success. Hundreds of people came and enjoyed it during the weekend. After that, we moved to “Museo Lunar” in Fresnedillas de la Oliva, where you may visit it now. We’re now working with INTA-CAB, who showed their interest; and together, we will be adding new posters and roll-ups with images and infographics. After that, who knows who will request the exhibition or where will it be hosted next.

Read about Spanish participation in MARS

Throughout the 21st century, humanity has successfully sent a total of seven missions to the surface of Mars; with the exception of China’s Zhurong, all led by NASA. The first generation was comprised of the Phoenix lander and the famous Spirit and Opportunity solar rovers, all out of service as of today. The most modern and still operational are the InSight lander and the thermonuclear rovers Curiosity and Perseverance, and all three are equipped with technology made in Spain.

InSight is a robotic platform about 6 meters long that studies the red planet firmly anchored to its surface. NASA launched InSight in early 2018, and by the end of the same year, it landed safely on Elysium Planitia. Once secured in position, InSight deployed its solar panels and instruments to begin investigations. InSight’s main goal is to study the depths of Mars to better understand how the planet formed in the first place and how much activity still persists within it. For this, it has a radio system, a seismometer, a heat probe, and some other additional instruments. All of them are aimed at the ground to study the radio signals, earthquakes, and heat that emanates or pass through the core, mantle, and crust of the planet. InSight has already sent us a lot of information of great scientific value, and although its solar arrays are now covered in dust and sand, drastically reducing its capabilities, it is still collecting data to help us better understand the nature of our neighboring planet.

While studying the internal structure of Mars is InSight’s main goal, studying its atmosphere is also part of the mission. For this reason, InSight is equipped with TWINS (Temperature and Winds for InSight), a weather station designed and built in Spain by the CAB (Astrobiology Center) and subsequently sent to NASA for implementation. TWINS is made up of multiple thermometers and wind sensors, as well as a barometer, a humidity sensor, and a magnetometer. The information provided by these instruments complements the data from the main instruments and, in addition, allows us to better understand the Martian atmosphere and informs us about the conditions that we could find in future manned exploration.

Ironically, there is only one TWINS; but the technology used by the CAB in its construction had already been tested previously on the Curiosity rover (and would later be applied to Perseverance).

As we said, Curiosity is a rover, a robot on wheels, the size of a small car, and designed to move across the surface of Mars and explore as it goes. NASA launched Curiosity in 2011, and in mid-2012 it successfully landed in Crater Gale. In all this time, the rover has traveled more than 27 km and has collected and retransmitted very valuable information. Among many others, it has been studying the atmospheric and geological characteristics and processes of Mars. It does this to help us better understand the planet, but also to look for biomarkers (indications of the present or past existence of life) and to assess the habitability of the environment. To do this, it is equipped with multiple cameras and spectrometers as well as other instruments such as a drill, a sample analyzer, and REMS.

REMS (Rover Environmental Monitoring Station) is a weather station installed onboard Curiosity. Like TWINS, REMS was designed and built in Spain by the CAB and later sent to NASA for implementation. REMS is Curiosity’s main instrument for studying the atmosphere of Mars. It is made up of multiple thermometers and wind sensors, as well as a barometer, a humidity sensor and an ultraviolet sensor. The information provided by these instruments allows us to better understand the red planet and its history and, once again, informs us about the conditions that could be found in future manned exploration.

Last but not least, Perseverance is a new sibling for Curiosity. Following its launch in 2020, Perseverance landed in Crater Jezero in early 2021 and has been studying its surroundings ever since. Its objectives are essentially the same as Curiosity’s and, consequently so are many of its instruments. Among them, the Spanish contribution could not be missing, on this occasion dubbed MEDA (Mars Environmental Dynamics Analyzer). MEDA shares objectives with REMS and equals or exceeds it in terms of atmospheric instruments. In addition, this 2.0 station is supercharged with dust and radiation cameras and sensors that are helping us to understand the important role that this dust plays in the Martian atmosphere.

Atmosphere and dust aside, Perseverance hides many other aces up its sleeve. To mention just a few of the experiments it has been conducting in the past year, Perseverance has managed to make breathable oxygen from atmospheric CO2, collected and stored samples that a later mission could bring back to Earth by the end of this decade, and has deployed and assisted Ingenuity, a small “helicopter” that has become the first vehicle to fly in an atmosphere other than Earth’s.

At this point, it might seem that in Spain we only know how to provide environmental stations. And while this would not be a source of shame, the reality is different.

The latest CAB success is the RLS (Raman Laser Spectrometer) which, as its name unequivocally indicates, is a Raman spectrometer. This instrument would eventually be able to study Martian soil samples in situ. By illuminating them with an extremely powerful laser and studying the light scattered by them, it would be able to identify their composition and provide key geological and mineralogical information for hundreds of investigations.

RLS is part of the laboratory on board Rosalind Franklin, the first rover that the European Space Agency (ESA) planned to send to Mars. Rosalind is named after the chemist and crystallographer Rosalind Franklin, whose studies helped us understand the structure of DNA. Like her, this rover was destined to revolutionize our understanding of life, since it was its main objective to search for and analyze biomarkers on the surface of Mars. Because it had such an ambitious objective, in addition to having the usual instruments in a rover of its category, Rosalind is, to date, the only rover equipped with a drill capable of penetrating up to two meters deep into the Martian crust and recovering radiation-free samples from the depths. These samples would then be sent to the onboard laboratory where Rosalind would search for biomarkers. It may seem like science fiction, but there were many who trusted that this mission would prove once and for all the existence of extraterrestrial microorganisms. However, recent events have dashed all hope. In fact, Rosalind was going to be launched in September 2022 by means of a Proton rocket to reach the surface of Mars on the Kazachok platform. However, since both the rocket and the platform are the work of Roscosmos, the Russian space agency and after the invasion of Ukraine, all collaboration with the attackers is being cut off; the project has been suspended indefinitely.

Although the cancellation of this final phase of the ExoMars project has been a blow to European (and Spanish) participation in this extraterrestrial exploration odyssey, the truth is that our environmental stations are still operational, providing crucial data day by day to improve our understanding of the planet; and one would like to think that we will find a way to revive the launch of Rosalind, or at least apply its technologies to a new, even more, ambitious mission.